Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, issue 7/2022.

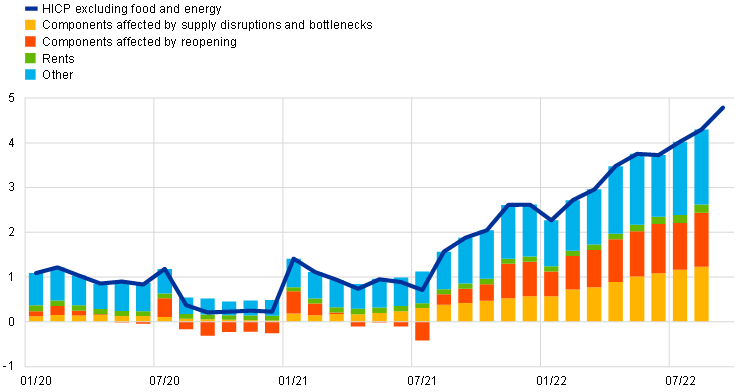

HICP inflation excluding energy and food (HICPX inflation) continues to rise and reached 4.8% in September 2022, according to a preliminary Eurostat release. Key HICP inflation, which also includes energy and food, rose to 10% in September. Energy and food account for about two-thirds of total inflation, and HICPX inflation accounts for about one-third. Both supply and demand factors played important roles in the rise in HICPX inflation. Persistent supply bottlenecks in industrial goods and input shortages, including labor shortages due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, led to a sharp rise in inflation. A recovery in demand since pandemic restrictions were lifted has also contributed to the current high inflation rate, particularly in the services sector. Together, the components of the HICP basket that are anecdotally more affected by supply disruptions and bottlenecks, and those that are more affected by post-pandemic economic re-opening, will lead to a of HICPX contributed to about half (2.4 percentage points) of inflation. Detailed data is available for the last month (Graph A). However, this ad hoc decomposition leaves out a large part of HICPX inflation and requires a further distinction between the roles of demand and supply factors in the euro area's underlying inflation. Since monetary policy primarily operates through the demand channel, it is important to assess the extent to which underlying inflation developments are attributable to supply or demand factors.

Chart A

Eurozone HICPX inflation breakdown

(annual change in percentage, percentage point contribution)

Source: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: Parts affected by supply disruptions and bottlenecks include spare parts and accessories for new and used vehicles, personal transportation equipment, and household furniture and equipment (including major household appliances). Masu. Elements affected by economic reopening include clothing and footwear, recreation and culture, recreational services, hotels/motels, and domestic and international flights. Latest observations are September 2022 (Flash) for HICPX and August 2022 for others.

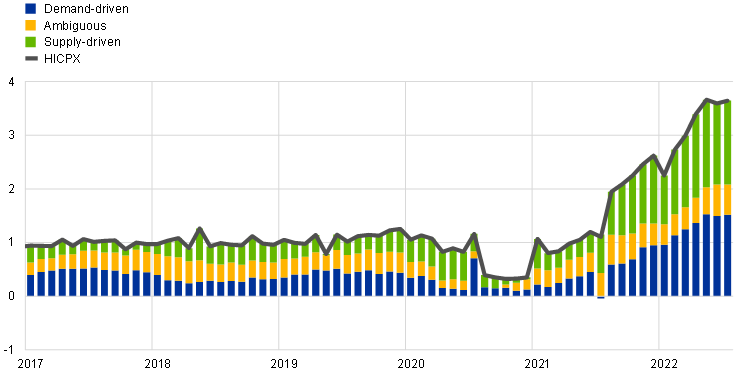

A disaggregated approach to analyze the role of supply and demand factors in each component of HICPX helps form a view about the overall role of supply and demand factors in HICPX inflation. This framework for monitoring inflation was originally developed for the United States by Adam Shapiro.[2] Trends in prices and economic activity are influenced by many factors, some of which can cause unexpected changes in supply or shifts in demand. HICPX Because it attributes the components of inflation (such as automobiles and lodging services) to a set that is primarily driven by supply factors or a set that is primarily driven by demand factors, this approach allows supply shocks to oppose activity and inflation. Take advantage of the fact that it affects direction. Demand shocks have an effect in the same direction. More precisely, in order to binary-attribute a component to either supply or demand, this approach takes into account the error that the time-series model makes at each point in time. If the price and activity errors have the same sign, their components are labeled with “.” Otherwise, it is referred to as “supply-driven.”[3] Only components whose errors are statistically significant are classified in this way. Components whose unexpected changes in price and activity do not differ significantly from the model's predictions are classified as ambiguous.[4] Based on this approach, the HICPX category for each month can be either primarily demand-driven (unexpected changes in price and activity moving in the same direction) or primarily supply-driven (unexpected changes in price and activity moving in opposite directions). movement in the direction). ) or as something vague. After this classification is done, the individual contributions of the components are summed (with consumption weighting applied) to derive the breakdown of his HICPX by month.[5] Note that this approach is binary and does not quantify how much demand and supply factors influence component levels. So, for example, supply factors may also play a role in component inflation trends that are classified as demand-driven.

To perform this decomposition, we need to collect data on activity and inflation for each HICPX category. Seasonally adjusted price indexes for each component included in HICPX are available on a timely basis at a detailed level (approximately 20 days after the end of each month for 72 HICPX components), but activity data for the corresponding components is not immediately available. Not available.[6] This complicates the analysis compared to the United States, where price and activity data are simultaneously available for each component of the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) deflator. To address this issue in HICPX, we used the sales index as a proxy for consumption after it was seasonally adjusted and deflated.[7] Based on this matching exercise, we can derive price activity pairs for all 72 HICPX subcomponents.[8]

This decomposition shows that the rise in Eurozone HICPX inflation starting in Q3 2021 was initially primarily supply-driven, but that over time demand factors gradually gained in importance. Suggests. In recent months, supply and demand factors have played roughly similar roles in HICPX inflation (Chart B). A robustness check using his HICPX series at constant tax rates (e.g. considering Germany's temporary VAT reduction in the second half of 2020) yields similar results.

Chart B

HICPX Inflation – Breakdown into Supply and Demand Factors

(annual change in percentage, percentage point contribution)

Source: Eurostat and ECB staff calculations.

Note: Seasonally adjusted data. Based on the approach developed by Adam Shapiro. HICPX inflation reflects the sum of demand-driven, supply-driven, and ambiguous factors and is calculated as the final total of contributions over the past 12 months. Price data is available for August 2022, but the sales series used as a proxy for activity is published somewhat later, so the latest observations are from July 2022.

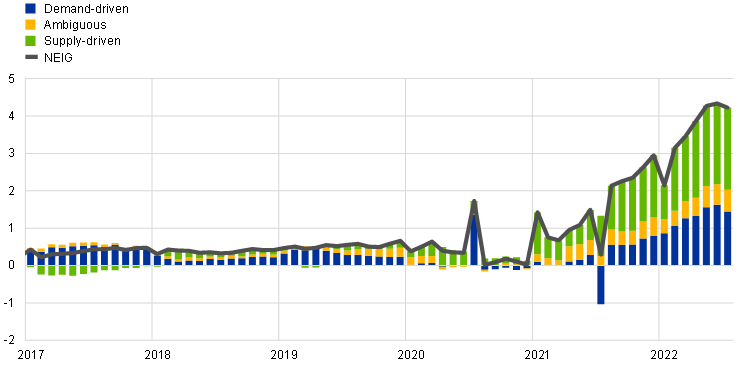

Looking at the main components of HICPX inflation, supply factors have played a slightly larger role in non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) inflation since early 2021 (Chart C). Changes in both demand and supply contributed significantly to the rise in NEIG inflation since fall 2021. Changes in supply did not play a significant role in the development of NEIG inflation from 2017 to 2020, but this is reflected in the fact that it became the main driver of NEIG inflation in 2021. Impact of supply bottlenecks. Since the second half of 2021, changes in demand have become increasingly influential as economic activity resumes, but supply factors remain dominant. Looking at individual components, the components that contribute the most to current NEIG inflation, such as automobiles and major household appliances, are classified as primarily supply-driven, while those such as furniture price increases are primarily demand-driven. It is classified as.

Chart C

Decomposition of NEIG inflation

(annual change in percentage, percentage point contribution)

Source: Eurostat and ECB staff calculations.

Note: Seasonally adjusted data. Based on the approach developed by Adam Shapiro. NEIG inflation reflects the sum of demand-driven, supply-driven, and ambiguous factors and is calculated as the final total of contributions over the past 12 months. Price data is available for August 2022, but the sales series used as a proxy for activity is published somewhat later, so the latest observations are for July 2022.

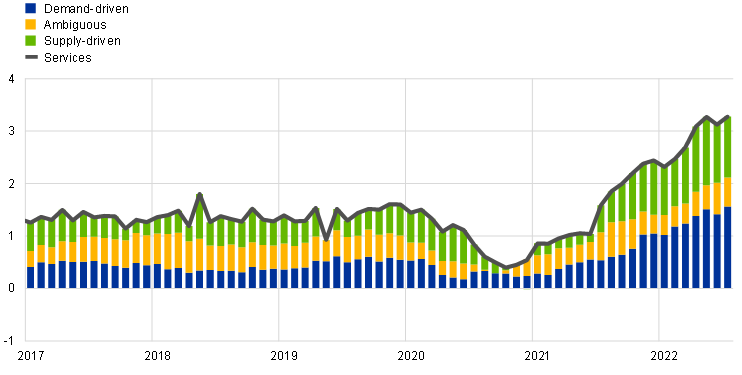

The strong rise in services inflation since mid-2021 has been driven by both demand and supply factors, with demand factors being more important for services inflation than NEIG inflation (Chart D). Demand and supply factors tended to contribute broadly and similarly to services inflation from 2017 to 2020, when services inflation in the euro area was very stable. The strong rise in services inflation since mid-2021 was initially driven primarily by supply factors. Contributions from mainly supply-driven components increased significantly in the second half of 2021, but thereafter he remained relatively stable until mid-2022. The role of demand factors in services inflation began to increase in the last months of 2021 and continued to increase until mid-2022, as the impact of economic reopening strengthened. More recently, the contribution of the primarily demand-driven component to services inflation has exceeded the contribution of the primarily supply-driven component. Looking at the components, we find that under the disaggregated approach, inflation in package travel and flights is primarily demand-driven, whereas inflation in home maintenance and repair services is primarily supply-driven. I understand this.

Chart D

Decomposition of service inflation

(annual change in percentage, percentage point contribution)

Source: Eurostat and ECB staff calculations.

Note: Seasonally adjusted data. Based on the approach developed by Adam Shapiro. Service inflation reflects the sum of demand-driven, supply-driven, and ambiguous factors and is calculated as the trailing sum of contributions over the past 12 months. Price data is available for August 2022, but the sales series used as a proxy for activity is published somewhat later, so the latest observations are for July 2022.

Although the disaggregated approach to the decomposition of HICPX inflation helps illustrate the role of supply and demand factors in the underlying inflation, there are important caveats to this method. The main advantage of this approach is that each HICPX component can be classified as primarily demand-driven or primarily supply-driven. This makes the results very transparent and allows them to be checked against other evidence available for the inflation development of the various components. This transparency is particularly valuable in the current environment of high uncertainty resulting from the impact of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine on activity and price changes. However, there are some caveats to keep in mind. First, there are various options for matching price and activity data. This is complicated by the fact that not all HICPX components have separate revenue series available (this includes the need for some HICPX components to match the same revenue series, especially if (There is an effect of NEIG inflation). Second, a disaggregated approach does not allow quantifying the magnitude of the supply and demand contribution of each component. For example, if the role of supply factors for components classified as primarily demand-driven is on average much larger than the role of demand factors for components classified as primarily supply-driven, this could introduce bias. There is a gender. Moreover, since the volume and price trends since the beginning of the pandemic are clearly exceptional and influenced by many special factors, it is important to build reliable models that can serve as a basis for classification based on signs of error. is becoming more difficult.