Their structural problems differ, but both result in the same outcome: subpar productivity, declining competitiveness and sluggish growth.

In a nutshell

- The eurozone’s two main economic engines are sputtering

- Tightened monetary policy and the war in Ukraine are partially to blame

- Longer term, structural economic problems pose the most daunting risks

The eurozone’s two largest countries, France and Germany, could drag the continent into a crisis. The year 2023 was bad for eurozone economies already, with sluggish overall growth a meager 0.6 percent. While short-term factors such as inflation and the necessarily tighter monetary policy can explain the latest developments, longer-term forces, especially in Germany and France, could influence future trends.

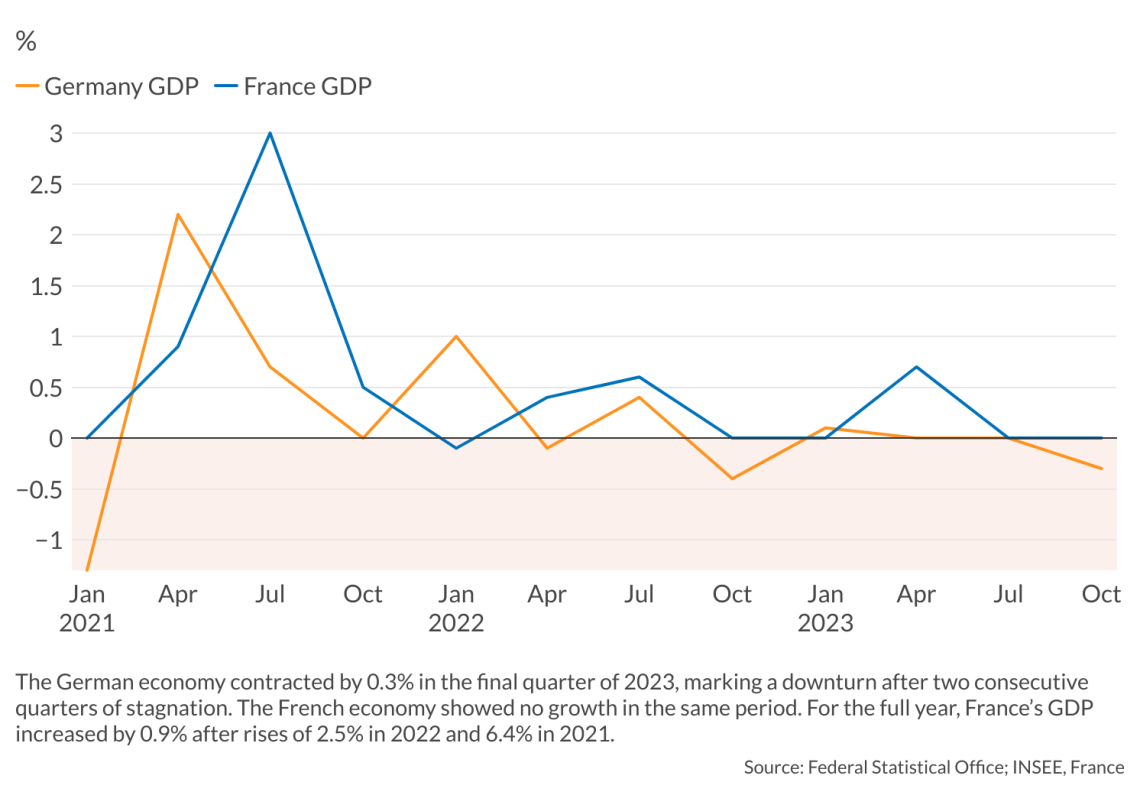

Germany is the eurozone’s leading economy (and third-largest in the world) and has been stalling lately, with its gross domestic product (GDP) shrinking by 0.3 percent in 2023. France, an economic drag for years, has also become a risk in terms of public finances. Both suffer from a form of inertia that represents a challenge.

Monetary squeeze

Part of the explanation for the quasi-recession lies in necessary monetary policy. Given high levels of inflation (10.6 percent in October 2022, and still at 4.3 percent in September 2023 but down to 2.9 percent in December), European Central Bank (ECB) policy has been, for more than a year now, focused on its primary objective of price stability – bringing inflation down to the target of 2 percent. To perform its duty, the ECB implemented a series of interest rate hikes until September 2023, when the rate on main refinancing operations was raised by 25 basis points (0.25 percentage points) to 4.5 percent.

The tightening was only apparent if one focused on nominal interest rates.

One could argue that high inflation meant real interest rates were still negative at least until October 2023 (when inflation dipped to 2.9 percent) – so the tightening was only apparent if one focused on nominal interest rates. However, the M3 money supply, the main monetary aggregate, has actually contracted an in the euro area for most of the third and fourth quarters, hitting its lowest point, at -1.3 percent, in August. Of course, there had been a significant increase in M3 during the Covid-19 pandemic, but, either way, these more recent policy moves have a contractionary effect on the economy, as they go hand-in-hand with a tightening of money creation via credit with various impacts.

With monetary tightening, households typically reduce consumption and spending projects, and there are fewer loans to access real estate property – with a profound negative impact on the construction sector. In France, 2023 marked a historic 7.8 percent drop in new construction activity, with its bellwether index – Construction PMI – hitting its lowest point, 39.6, in January.

Facts & figures

Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI)

Produced by HCOB (Hamburg Commercial Bank) and compiled by S&P Global, the PMI is a good indicator (and predictor) of economic activity. When above 50, the index reflects growth of manufacturing and commercial activity. When below 50, it points toward recession – the lower the figure, the worse the coming trouble.

In January 2024, the eurozone composite PMI was at 47.9, well below 50 for the seventh month in a row. Manufacturing PMI was 46.6, up from a worrying 44.4 in the previous month (a 10-month high); the PMI for the services sector was only 48.4 in December 2023.

Major eurozone economies have recorded low PMI scores for several months running, like Germany (composite PMI of 47.1 in January, after the highest point in December, even though its manufacturing PMI is recovering at 45.4 – an 11-month high). Italy fared only slightly better last December (PMI 48.1), while France scored 44.2 on its composite PMI in January and a still-worrisome 43.2 manufacturing PMI).

Businesses see the cost of financing investments rising, the availability of financing contracting and their prospective demand declining. As a result, they invest less, which in turn means fewer sales for businesses selling fixed capital goods, such as machinery. Access to short-term credit for business working capital requirements is more limited, with an intensified risk of bankruptcies. In short, the credit crunch is taming inflation but, unfortunately, is also pushing the system toward a recession.

Eurozone demand shocks

The eurozone economy has also been subject to demand shocks besides the monetary dimension. Obviously, inflation makes goods and services more expensive, so it leads to less domestic demand but also less demand abroad as production for exports is less competitive (even if the euro falls slightly) – an important aspect for Germany, whose exports account for nearly half of its GDP.

Also, declining demand from China, Germany’s biggest trade partner – after almost three years of lockdowns – has meant fewer exports, particularly for German mainstay car makers. New protectionist policies, like subsidies, in the United States (the Inflation Reduction Act) and China also have contributed to European Union-made products becoming less competitive. China’s competition in the automotive and machinery segments is seriously challenging Europe.

The eurozone economy has also been bombarded with supply shocks for the past three years, inducing direct cost increases or maladjustments for its businesses.

Falling demand hurts not only big German factories but also all the suppliers in their value chains, upstream in Germany and abroad (in Spain, but mainly the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland, as car manufacturing brands such as Volkswagen or Mercedes have factories there), who in return will buy less from Germany and other parts of Europe, in a self-reinforcing vicious cycle.

With rising prices, European standards of living have suffered. However, uncertainty and a lack of confidence have slowed consumption, so households save more, which pulls demand further downward. Aging demography, especially in Germany and France (where 2023 marked the lowest birth rate since 1945), is also contributing to this trend, notably in the context of uncertainty about future pensions.

Supply shocks

The eurozone economy has also been bombarded with supply shocks for the past three years, inducing direct cost increases or maladjustments for its businesses. The PMI has reflected this recently, especially for France and Germany.

The first obvious shock concerns energy supplies. Energy is the lifeblood of the economy. The war in Ukraine and the partial severing of ties with Russia has sent energy bills soaring and countries scrambling for alternative gas supplies. Natural gas was earlier seen as a “bridge” fuel (that emitted less carbon dioxide than coal and oil in energy generation) to substitute the “dirtiest” fuels until economies could entirely switch to renewable energies.

Thanks in large part to the lack of foresight by former chancellors Gerhard Schroeder (1998-2005) and Angela Merkel (2005-2021), Germany had made itself especially dependent on Russian gas for its energy-intensive industries. The replacement of cheap Russian gas with alternatives like liquefied natural gas (from the U.S. or Qatar) has proven too costly for many companies. The problem was compounded by a quirk in the design of the EU energy market.

Facts & figures

The impact of gas on electricity prices

Gas was a determinant of the European electricity market’s “marginal cost” pricing system. Gas turbines are the most flexible: they produce the “marginal” (last) unit when supply needs to meet demand (rather than much less flexible nuclear or intermittent wind and solar). Therefore, if gas prices increase, the marginal cost goes up, and electricity prices automatically increase, translating into higher costs for businesses. The EU’s recent reform seeks to address this issue.

Even before the war in Ukraine, the various “energy transition” policies promoting renewable sources of energy – such as Germany’s Energiewende – had proven uneconomical and not practical enough. Following the political trend, France, traditionally a major producer of electricity, turned away from atomic power in the mid-2010s, aiming to reduce nuclear’s share in its electricity mix from about 70 percent to 50 percent by 2025. The policy was abandoned in 2023, but it had disincentivized investment in the sector, leaving France’s nuclear power infrastructure in a sorry state.

The costs, stupid!

The cost increases – despite government aid packages to companies – and rising uncertainty about energy supplies have inevitably deterred investment. Big German companies in the chemical sector, like BASF, opened factories in Asia or the U.S. Chemical industry activity on German soil has fallen by 20 percent in two years. Ammonia and aluminum production, for instance, had to be drastically reduced, compensated by imports from China.

However, many small “Mittelstand” (medium-sized) companies, which are a pillar of the German industrial model, cannot offshore production, so they cut back output. Europe has a “Green New Deal” that is supposed to promote reindustrialization via green transition; but it is at risk precisely due to these higher costs.

Facts & figures

Germany and France, GDP growth rates

The second negative supply shock is the effect of inflation (other than the one caused by energy price increases) on businesses’ costs. The various programs to support enterprises have gradually disappeared, sometimes unveiling the reality of “zombie” companies – unable to meet their expenses from normal operations. France, for example, has a record number of failing companies. If one leaves energy issues aside, inflation has had other causes from a “cost-push” angle: the disruptions of various supply chains for more than three years, the closing of China, its essential factories and ports and problems with semiconductors.

German inertia

These generally short-term factors have caused deindustrialization. However, the future of the EU will also largely depend on the responses that Germany and France give to their structural issues affecting supply.

While Germany has long been famous for its “Deutsche Qualitat” (German quality) manufacturing, the tables are turning when it comes to its leading exports: cars (automotive production represents 5 percent of its GDP). The “dieselgate” scandal in the mid-2010s should have been a warning. However, the country’s automobile champions lagged in innovation, allowing several Chinese and one U.S. automaker, Tesla Inc., to attain very significant competitive advantages in electric vehicles.

Cutting-edge high-tech and digital industries seem not to have successfully entered the framework of the “engineers’ culture” of the nation. Its manufacturing sector, more broadly, which represents 24 percent of German GDP, has become complacent and thus more vulnerable. The country’s aging workforce is becoming less productive, and its capital stock is dated, too.

One crucial challenge is whether Germany will switch back to Russian gas after the war, as some German politicians wish, and go back to business as usual.

This inertia is also found in the public sector, which is plagued with a suboptimal bureaucracy and persistent difficulties in entering the digital age. From the use of 20th-century fax machines to slow authorization procedures for businesses, or from a decaying public energy system to communication and transportation infrastructure, the country seems to lag.

Scenarios

Teutonic shifts?

The scenarios for Germany depend first on monetary policy that should be more accommodative again with the decline of inflation in the fourth quarter of last year (despite a rebound in December) and the recession. ECB President Christine Lagarde said in January that rates would not be lowered before the summer of 2024. The real impact of monetary policy appears about 18 months after a change.

As for foreign demand, it seems that the Inflation Reduction Act is here to stay and Chinese competition in electric vehicles and machinery is as well. However, according to a recent study by the KIEL Institute,“decoupling” from China could be excruciating in the beginning and then manageable in the longer term.

On the geopolitical side, one crucial challenge is whether Germany will switch back to Russian gas after the war, as some German politicians wish, and go back to business as usual. Poland, Ukraine and the Baltic states oppose this move and are considering a post-war alliance protected by the U.S. If former President Donald Trump is elected on a protectionist platform in the U.S. in November, it could make Germany’s – and Europe’s – trade and growth issues more acute.

Inertia from the ruling coalition led by Chancellor Olaf Scholz, given its heterogeneous nature, could hinder any serious pro-growth plan. For example, the discussions last December between the liberal Federal Minister of Finance Christian Lindner and the greens-designated Vice Chancellor and Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Robert Habeck led to an unwieldy compromise – which was one of the triggers of the massive farmer protests that began in January.

Some economists think that, given Germany’s lower (compared to the EU average) public debt and its reputation for financial prudence, the November 2023 court-imposed restrictions on government spending rules could be relaxed to enable necessary public infrastructure investments that could support growth. More strikes could add to the economic headwinds. Economy Minister Habeck admitted in February that the German economy had had a “dramatically bad” performance. The country’s 2024 GDP growth forecast has been lowered to a pitiful 0.2 percent.

Most likely in Germany: Lasting inertia

One longer-term worry is that the industrial and commercial successes of the past two decades – the source of massive fiscal surpluses – made all of Germany, not just its auto industry, complacent. To combat this, experts advise a host of solutions, such as linking the retirement age (already at 67) to life expectancy, increasing investment in education and training, focusing immigration on skilled workers, as well as digitization and drastic cuts in red tape and new regulations in capital markets to promote funding for small businesses.

The inertia, coupled with shortages of skilled labor because of an aging population and educational issues, could last. A society does not change that easily, especially if it is aging. And as recent protests have shown, Germans will not accept “reforms” so meekly.

French woes

While again calling Germany the “sick man of Europe” as in the late 1990s would probably be an exaggeration, as it now has low unemployment and trade and fiscal surpluses, some wonder whether the labeling could apply to France.

The French unemployment rate reached its lowest point in the past 40 years in the fourth quarter of 2021, but it is still high compared to EU standards, and has very recently risen to 7.4 percent. France’s relatively generous social system is weighing heavily on labor costs. It shares some of Germany’s challenges: an aging population, “mismatch unemployment” (lack of congruence between job vacancies and job seekers’ skills), brain drain, a lack of innovation and a decline in education standards and skills, all pointing to a fall in productivity figures.

The country’s deindustrialization has been well underway for the past 40 years, its manufacturing sector now representing just over 10 percent of GDP. The government does have plans to reindustrialize, but despite a few promoted projects, the already-mentioned record number of business bankruptcies does not reflect a reindustrialization boom. And France’s construction sector, crucial to the economy, has been severely hit by the credit crunch.

Even more worrying is France’s inability to curb its ailing public finances. Its bloated, not very efficient public sector (public spending is still at 58 percent of GDP), permanent deficits (4.4 percent in 2024) and untamed public debt (111 percent of GDP) are acting as a powerful drag on the economy.

French awakening?

The scenarios on overcoming inertia depend on France’s popular resistance to change, in large part due to its dysfunctional democracy resulting in an inability to build consensus between opposing interests and social groups.

Prime Minister Gabriel Attal, the country’s youngest ever, says he wants “full employment” in 2027 by promoting the value of work, “simplifying” the business environment and reducing public deficits. Yet, his appointment in January 2023 was essentially a political move before European elections. Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire remains. Reforms may, as before, amount to a shell game. The new December 2023 deal on budget rules in the eurozone could even serve as a pretext for France to push back on these rules. Recent strikes will undoubtedly weigh in the same direction.

Several experts, like French economist Marc Touati, think its sovereign debt rating should be downgraded further (after Fitch’s lower rating in April). Given the size of the French economy and its public debt (one-fourth of the entire eurozone debt), a downgrade could trigger a severe crisis in the eurozone.

Most likely in France: Economic and political impasse

Despite disinflation and slightly recovering PMIs in the last two months, France’s perspectives are not great. In mid-February, Minister Le Maire lowered the country’s GDP growth forecast for 2024 to 1 percent from 1.4 percent. This matches the IMF estimate, while the OECD is more pessimistic at 0.6 percent. Mr Le Maire announced the need of 10 billion euros in public spending cuts; it is as if the rating agencies had unofficially warned him about their possible next move in April.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.